PHISTLE: A Standardised Humour Pedagogical System

There are many known benefits of humour in classroom, including enhancement of student engagement, increase of motivation and creativity, improvements of attention and performance and the relieve of stress [1-8]. Humour is one of the best ways to induce positive emotions and to promote emotional well-being in students [9], and it is widely recognized as a common trait of many excellent teachers. Unfortunately, not every teacher is naturally humourous, and even naturally humourous teachers may not consistently come up with appropriate jokes in every class. Furthermore, although some believed that spontaneous humour is “the best humour”, spontaneous humour is difficult to replicate and its outcomes are difficult to predict as well.

To overcome these problems, we developed a standardised humour pedagogical system. In this system, planned humour of specific types are incorporated in specific ways at specific frequencies in lectures/lessons, so that we can consistently generate positive outcomes that are predictable and replicable. We termed this system “Planned Humour Incorporation System for Teaching and Learning Enhancement” (PHISTLE).

An obvious advantage of PHISTLE is that it acts like an “add-on” on top of our existing lecture-based system of teaching. Although flipped-classroom, blended learning, and other innovative teaching approaches are undeniably beneficial, most courses in universities right now are still lecture/lesson-based. PHISTLE incorporates content-related humour into lecture PowerPoints, so it can be easily applied to both face-to-face and online/mixed-mode teaching (especially during waves of the COVID-19 pandemic). Another advantage is that its basic products include lecture/lesson notes in the form of PowerPoint presentations. Therefore, they are sustainable, and can be reused year after year.

How Does Humour Enhance Learning?

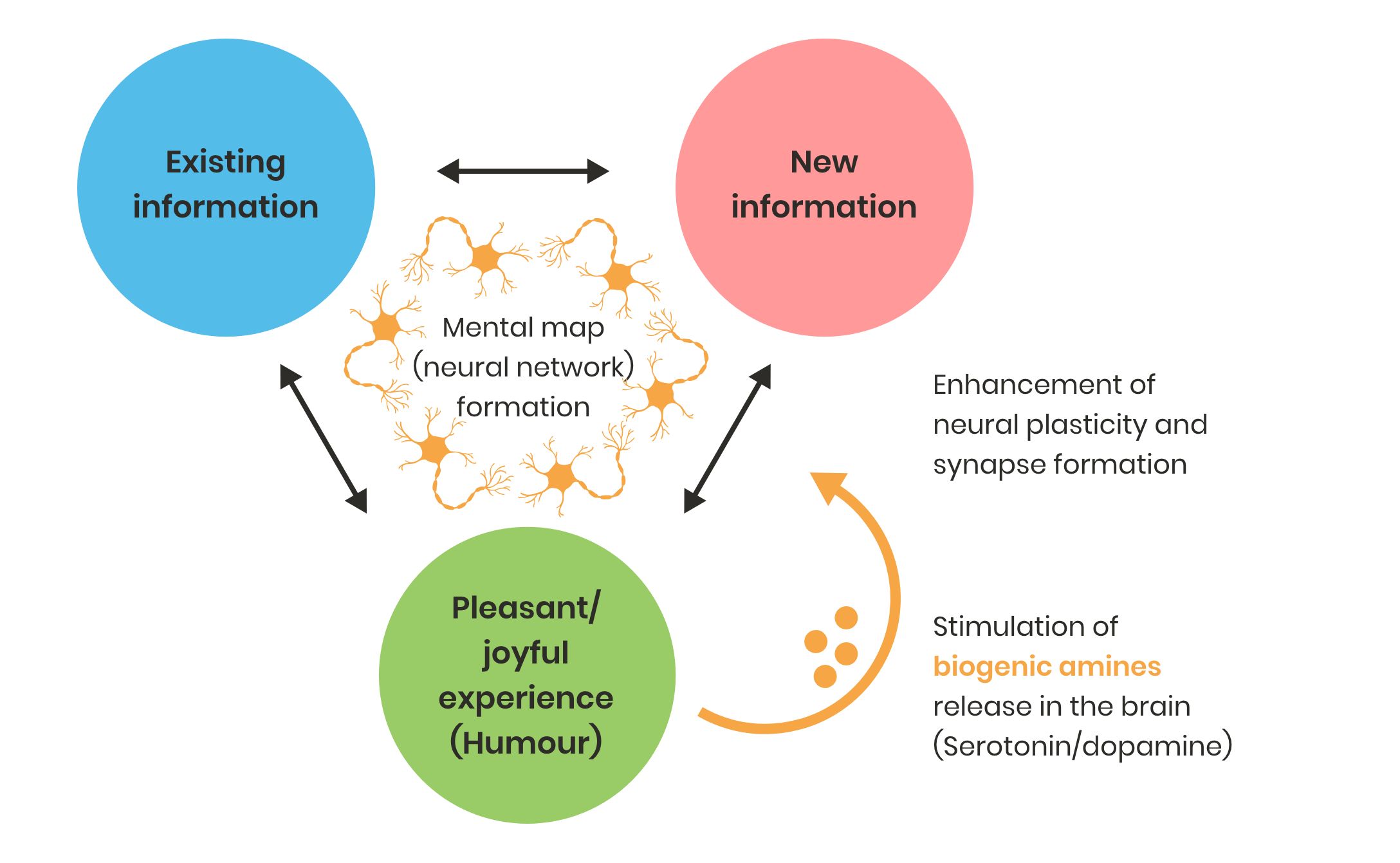

To better understand how humour can enhance learning, we need to first understand how learning is achieved. Cognitivism is a classic learning theory that views learning as a process in which people receive “new information” via sensory input, and then seek ways to understand it by relating and incorporating it into “existing information” in the learner’s memory. Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development was that children build “mental maps” in their brains for understanding and responding to their experiences within their environments [10]. Piaget believed that some kinds of cognitive structures were interrelated in the brain, and new knowledge(new information) would have to fit into the existing system (existing information) for it to be understood and consolidated. These mental maps are changed each time new information is incorporated, and it is this integration of new information that forces the cognitive structures to become more elaborate. Piaget’s theory contributed to a key concept of cognitivism, which recognizes learning as a process that constructs these complex mental maps inside the learner’s brain, and it explains the development of human intelligence.

Interestingly, previous studies found that positive emotions, such as happiness, interest and satisfaction, can effectively extend an individual’s attention span, enhance cognitive flexibility, and expand cognitive maps [11,12]. It was found that emotional arousal affects learning and memory via certain “factors” that modulate memory encoding and memory consolidation [11]. In modern neuroscience, we now recognize these “mental maps” to be “neural networks” involving neurons forming synapses with one another in the brain. As for the mysterious “factors” that can modulate memory, one such factor is believed to be biogenic amines that are released in the brain during positive emotions. Biogenic amines, such as serotonin and dopamine, are known to regulate synaptic plasticity, and synaptic plasticity is widely believed to be the cellular basis of learning and memory [13].

The extensive research of biogenic amines’ influence on synaptic plasticity can date back to Eric Kandel’s Nobel prize-winning work back in the 1960s, which involved the deciphering of long-lasting synaptic changes in the sea slug, Aplysia, in response to the plasticity-enhancing effect of serotonin [14]. In fruit flies, past studies have also shown that some of biogenic amines can modulate synaptic plasticity, and may play a role in learning and memory [15,16]. In humans, serotonin is known to be involved in emotions and motivation, as well as modulating learning and memory [17]. Dopamine, on the other hand, is another biogenic amine mostly associated with positive emotions [12]. Dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (a key component of the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system in the brain) has been shown to promote learning and motivation [18].

Humour has been shown to stimulate neuronal activities in the human nucleus accumbens [19]. In this region of the brain, fast dopamine fluctuations (in the order of seconds) support learning [20], whereas much slower dopamine changes (in the order of minutes) are involved in motivation [21,22]. Combining these neuroscience findings with the cognitivism learning theory, we developed a working model of how biogenic amines from positive emotions facilitate the formation of a neural network, connecting the (1) existing information, (2) new information, and (3) the pleasant/joyful experience (see figure below). After the formation of this neural network, when a person recalls the memory of any one of the three components, it will lead to neural signals being sent to the other two, which further reinforces the connections (classic Hebbian theory). Through this mechanism, learning and memory can be enhanced.

Working model of how biogenic amines from positive emotions facilitate the formation of a neural network in the brain of a learner. The model generated by integrating molecular neuroscience into the cognitivism learning theory. Pleasant/joyful experience stimulates the release of biogenic amines in the brain, which in turn facilitate the formation of a neural network among (1) existing information, (2) new information and (3) pleasant/joyful experience. Once the neural network is formed, firing of one group of neurons will likely result in the firing of the other two groups, resulting in reinforcement of synaptic connectivity and thereby memory as well.

Our Logo

In the central part of the logo of the HETL Community of Practice, the 3 neurons represent “existing knowledge, new knowledge, and joyful experience” connecting with one another. The “molecules” (which also happen to be the cell bodies) represent biogenic amines released during the joyful experience that enhances neuronal connectivity.

The curves and circles outside represent “people of the community” embracing the central part, the two “people” also happened to form a “big smiley face”, which underpins the joy and fun in learning.

- Wandersee, J.H. (1982). Humor as a teaching strategy. The American Biology Teacher, Vol. 44, No.4.

- Powell, J.P., & Andresen, L.W. (1985). Humour and teaching in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 10(1), 79-90.

- White, L.A., & Lewis, D.J. (1990). Humor: a teaching strategy to promote learning. J Nurs Staff Dev. 6(2), 60-4.

- Garner, R.L. (2006). Humor in pedagogy: How ha-ha can lead to aha! College Teaching, 54(1), 177-180. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Banas, J.A., Dunbar, N., Rodriguez, D., & Liu, S. (2011). A review of humor in education settings: Four decades of research. Communication Education, 60(1), 115-144.

- Segrist, D.J., & Hupp, S.D.A. (2015). This class is a joke! Humor as a pedagogical tool in the teaching of psychology. Society for the Teaching of Psychology’s Office of Teaching Resources. Retrieved from http://www.teachpsych.org/Resources/Documents/otrp/resources/segrist15.pdf.

- Appleby, D.C. (2018). Using humor in the college classroom: The pros and the cons. Psychology Teacher Network.

- Bakar, F., Kumar, V. (2019). The use of humour in teaching and learning in higher education classrooms: Lecturers’ perspectives. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 40, 15-25.

- Crawford, S.A. & Caltabiano, N.J. (2011). Promoting emotional well-being through the use of humour. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(3), 237-252.

- Piaget, J., Boring, E.G., Werner, H., Langfeld, H.S., Yerkes, R.M. (1952). A History of Psychology in Autobiography, Vol IV., Worcester: Clark University Press, pp. 237-256.

- Hamann S. (2001). Cognitive and neural mechanisms of emotional memory. Trends in cognitive sciences. 5(9):394-400.

- Yin, J. (2019). Study on the Progress of Neural Mechanism of Positive Emotions. Transl Neurosci. 10: 93-98.

- Dismukes, R.K. & Rake, A.V. (1972). Involvement of biogenic amines in memory formation. Psychopharmacologia, 23, 17-25.

- Kandel, E. R. and Spencer, W. A. (1961) Electrophysiological properties of an archicortical neuron. Problems in Electrobiology, Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 94: 570–603.

- Koon, A.C., Ashley, J., Barria, R., DasGupta, S., Brain, R., Waddell, S., Alkema, M.J., Budnik, V. (2011). Autoregulatory and paracrine control of synaptic and behavioral plasticity by octopaminergic signaling. Nat Neurosci. 14(2):190-9.

- Koon, A.C. and Budnik, V. (2012). Inhibitory Control of Synaptic and Behavioral Plasticity by Octopaminergic Signaling. J Neurosci. 32(18): 6312-6322.

- Menesses, A. and Liy-Salmeron, G. (2012). Serotonin and emotion, learning and memory. Rev Neurosci. 23(5-6):543-53. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2012-0060.

- Hamid, A., Pettibone, J., Mabrouk, O. et al. Mesolimbic dopamine signals the value of work. Nat Neurosci 19, 117–126 (2016). https://doi-org.eproxy.lib.hku.hk/10.1038/nn.4173.

- Mobbs, D., Greicius, M.D., Abdel-Azim, E., Menon, V., Reiss, A.L. (2003). Humor Modulates the Mesolimbic Reward Centers. Neuron, 40(5), 1041-1048.

- Steinberg, E.E. et al. (2013). A causal link between prediction errors, dopamine neurons and learning. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 966-973.

- Cagniard, B., Balsam, P.D., Brunner, D. & Zhuang, X. (2006). Mice with chronically elevated dopamine exhibit enhanced motivation, but not learning, for a food reward. Neuropsychopharmacology 31, 1362-1370.

- Salamone, J.D. & Correa, M. (2012). The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron, 76, 470-485.